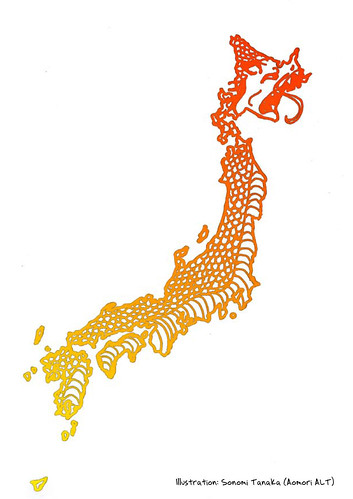

A dragon slumbers beneath the Japanese archipelago. If you were to look at the profile of the islands from space, you might be able to see the shape of it in them. Then again, you might see anything but a dragon and wonder what fit of creative madness spawned the legends of this beast.

Regardless, in Japan there is an old myth that the islands are actually perched on the back of a sleeping dragon. If you humour the idea, screw up your eyes, and look at a map of Japan from across a crowded room, maybe you’ll catch a glimpse of it. And, if you did, you might further conclude that, were these islands to be a dragon, the shape of the island of Hokkaido would be the best fit for a dragon’s head.

It’s not just the shape of the islands that lends credence to the myth. There is also the fire at the heart of Japan: the fact that our string of islands is just one more line of volcanoes in the pacific Ring of Fire. When you remember this, what better symbolic creature is there for an archipelago with magma boiling away at its core than a dragon?

Grandiose Japanese storytellers would dust off this old myth at parties to impress foreigners. They would say that the islands of Japan rested on the back of a sleeping dragon, or that a dragon slumbered under the islands, or that the islands themselves were a dragon. It was the Dragon that brought luck to the Japanese: the Dragon that would sustain them through their hardships, the storytellers would claim, hardly believing the thing themselves but reveling in the wonder it bred in the eyes of their audiences.

It was a fun little bit of myth and it never had any real consequences until back in the 1940s when someone had the idea of building a train tunnel from Aomori to Hakodate, joining the island of Honshu to the island of Hokkaido with a fixed, underwater rail link. Clever men bored beneath the Tsugaru Straight, holding nothing back. With their clever machines they dug three separate tunnels. When their clever machines couldn’t advance, they resorted to clever alchemies of channeled fire. And when even their powdered explosions failed to clear the way, they moved the stone by strength alone. They dug their tunnel deeper than anyone else ever had, they dug it longer than anyone else had ever imagined. They even built shrines to their own cleverness in the bowels of it: the only two train stations to ever be built beneath the ocean floor, each of them housing museums to safeguard the records of the men’s exploits.

All the while, it is doubtful that any of them thought twice about what they were doing. Their minds had grown sharp and quick over their years of schooling, grown to places where kappa and tanuki and obake were figments: unrealities meant to scare children straight. Those minds were so filled with cleverness that they had little room for story—for myth—and few among them remembered the tale they’d been told in their youth about the Dragon beneath Japan.

The Dragon, for its part, remembered.

And when those clever men completed their tunnel, linking the north and the south, and sent through the first trains on March 13, 1988, there were others who remembered, too. The people who used to tell the story of the Dragon to impress foreigners at parties, they wondered what if there really was a Dragon? What if Hokkaido was its head and Honshu its body? Wouldn’t this newly opened Seikan tunnel that bored so deeply through the rock beneath the islands be a slit across its throat? Would it not demand some sacrifice for the insult?

The Dragon’s ire was slow in building. It came gradually as Japan moved into the 1990s, and the nation found the luck it had been riding since the 1950s drying up. The bubble burst, and Japan descended into financial turmoil that lasted long into the new millennium. All the while those same men who would uproariously tell the tale of the Dragon to entertain the foreigners began whispering it to their Japanese friends, speaking suppositions about whether all this financial upheaval after so much gain might not be the Dragon finally turning on the Japanese people.

Now the sons and grandsons of those first clever men labour industriously to bring new wonders to the Seikan tunnel: the lightning miracle of Shinkansen. By 2015, they aim to traverse the tunnel ever more rapidly, ever more frequently. And the storytellers—now old and grey—begin to wonder what new ire the Dragon will manifest at this fresh insult—how the Japanese people may be made to understand the danger of sacrificing myth to the modern.

No comments:

Post a Comment