Friday, June 04, 2010

Janken

Tuesday, March 02, 2010

Why Japan Always Wins

With this being exam time for my junior high school students, the awesome school lunches that they and we teachers receive have been cancelled for the next few days. I was dutifully informed of this when I was given my schedule for this month, but as that was about two months ago, I promptly forgot and showed up with only an orange and an apple for lunch today.

Crap.

No matter, though, as apparently I wasn’t the only one, and a bunch of teachers lumped together and placed an order with the very delicious Minato Sushi in town.

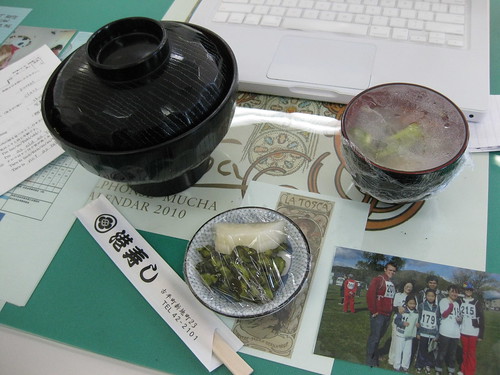

When one of the proprietors showed up with our delivery, I don’t know what I was expecting, but it certainly wasn’t to have the orders bundled to serving trays with tied handkerchiefs, the food within still steaming in real, non-disposable bowls and plates from the restaurant. They delivered the food, took our cash, and left, only to return about an hour later to collect the flatware.

That they would bring the food in real dishes and leave them with us…It’s not a big thing, but it’s a nice thing. It’s a small-town-home-made thing; a fresh thing and a real thing.

It’s the kind of thing Canada just can’t compete with.

Friday, November 20, 2009

ITADAKIMASU!

In Japanese elementary and junior high schools, students receive a free prepared lunch every day, delivered to their classroom and served up by their peers. The teachers at the schools benefit from the same system, though they have to pay for their lunches. Regardless, not having to worry about packing a lunch is a fantastic experience. And, what’s more, the stuff that they serve up at the schools is often above par when compared to the cafeterias of Canadian schools. I mean, it could well be the Japanese equivalent of cafeteria crap in the eyes of native Japanese. However, if that’s the case, we thankfully set our bar far lower in Canada when it comes to deciding what’s fit to serve our young, growing, academic minds.

The culinary abominations of my own high school cafeteria have left me feeling like Japanese school lunches are meals fit for a king. They all tend to be at least “alright,” and at times they even nudge into “good” territory. The fact that I don’t have to make them myself and don’t have to pay for them up front also does wonders for the flavour. And, at the elementary school, the school lunch is further improved by the fact that I get to eat it in one of the classrooms with the actual students.

And when you sit and eat with the students, you can really catch glimpses of their growth. The younger grades at the elementary hardly ever clamour for seconds, electing instead to feed them to big fat gaijin sensei (that would be me). Up around grade 4, the students start developing an appetite, and by grade 6 they are screaming for the left over scraps and fighting furious janken1 wars for half a tempura shrimp. By the time the kids reach junior high, their bottomless teenage stomachs have them banging down the door of the teacher’s room on days when lunch is particularly good, looking for any scraps we happen to leave behind.

There's also the whole ceremony around lunch here. When you're eating in the classrooms with the kids, one of them will be assigned to the role of class leader for the day. This person usually prompts the rest of the class for greetings (every Japanese school period starts with students greeting their teacher, and every Japanese school period ends with students saying goodbye to their teacher), and I'm pretty sure this leader can be taken to task when the rest of the class is acting up.

When it comes to lunch, this leader is responsible for beginning and ending the meal. It begins with a raucous "ITADAKIMASU!", which is thunderously echoed by the rest of the students. It roughly translates to "thank you for this meal," but it is far more symbolic than that, referencing buddhist worship and the idea that an animal dying to feed you is one of the greatest sacrifices it could make. When you hear it every day, it starts to lose its meaning and becomes a bit of a joke as students bellow it at the top of their lungs, but as soon as you make the mistake of starting to eat before it has been said, you quickly realize how important this ceremonial element is (and that realization makes you feel like a big, stupid gaijin pretty quickly!). And, once the final student is done eating, the same class leader will clap their hands and yell "gochisosamadeshita!", which loosely translates to "it was a real feast!" and serves as the formal ending to the meal.

Just like with ever other pedestrian event in Japanese society, you've always gotta have an opening and closing ceremony.

In addition to sometimes being rather tasty, the lunches provide a degree of entertainment. Take today, for example, when I was served with a riddle, battered in a crunchy mystery coating, seasoned with some tasty enigma sauce. We got a 8-10” hotdog bun, a plate full of fried noodles, some of the awesome-fire-engine-red pickled ginger, and the meagerest scrap of Japanese bacon-cut pork you’ve ever seen. That last one, as we painfully discovered one hungover Sunday morning, is a clever ninja ploy that looks just like western bacon but tastes like a really skinny piece of pork. Yeah, it doesn’t sound so bad until you put it in your mouth expecting bacon, and you find out that it’s not.

That was my lunch, and just as I was about to set into it with the provided fork, I noticed the teacher across from me cramming the piece of faux bacon, ginger, and noodles into the big hotdog bun. I suspected this might be some clever ploy to make me look like the foolish gaijin barbarian everyone suspected me of being, but I looked around and saw everyone else was doing it. Apparently the carb-tastic meal was called yaki soba pan, which directly translates to “fried noodle bun” (duh). Why you’d eat fried noodles in a bun is beyond me, but that was the way of it.

1Janken is the Japanese version of rock-paper-scissors. But, when compared to the intensity and form of janken, rock-paper-scissors resembles a series of aimless, spasmodic flailings.