She’s the one who graciously invites me into her home every Monday for elaborate, Japanese dinners, and she’s one of the loudest cheerleaders behind our International Society. With good reason, too, as she’s traveled to/lived in something ridiculous like 25 countries. In Canada, such a feat would be impressive. In a sleepy fishing village in Japan, such a feat is pretty much unheard of. So, every time one of these international events rolls around (and that’s more often than you might think), she makes sure I’m going to be there, and she goes out of her way to invite international students in from the Universities of Sapporo. She hooks them up with homestays and Japanese meal, and she encourages them to present their particular corners of the globe in front of gathered townsfolk.

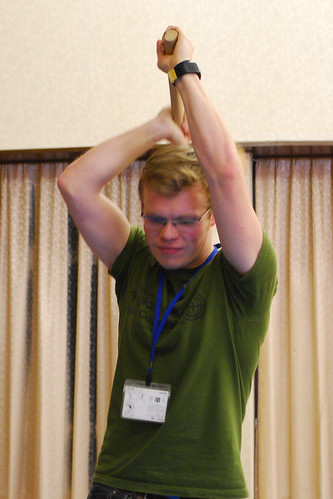

And last Sunday she had the students in for the Mochi Party. It’s not really any surprise that the students decided to show up, though, as a mochi party involves hefting a wooden mallet high over your head before bringing it down with gusto on cooked rice in massive stone mortar. Who wouldn’t want in on something like that?

Again and again you pound the rice in an action the Japanese euphemistically refer to as “whacking the rabbit,” all the while trying deftly to avoid the hands of the person who’s kneading the ever-stickier rice paste for you.

Don’t be confused by that last bit. You’re not supposed to break your whacking rhythm to wait for the Kneader to get his hands out of the way. In fact, you’re pretty much supposed to aim for the hands and hope they’re not there when your mallet connects with that sticky THUD. So artful is the rhythm of this perilous dance that professional Mochers (mochi-ers? moochers?) heft the hammer blindfolded, without any concern for the frantic kneaders below.

To make the whole thing even more fun, after all this whacking you actually get to eat the fruits of your surprisingly-intensive labour, one round, dense, choke-tastic mochi ball at a time.

Just as it was no surprise that the international students wanted to get in on this edible form of whack-a-mole, it should have been obvious that some of my JET buddies would want to be part of the action. Lindsay, Roz, and Heather showed up for the event, further bolstering Asano-Sensei’s contingent of gaijin-on-display. They all performed wonderfully in the whacking, shaping, and eating parts of the day’s events. Here’s proof of that.

Here’s a look at the fruits of their labour, more for Craig than anyone as he’s shown himself to have an unnatural love for this particular Japanese food item.

And this one's for me.